A Short History of the Department of History

About

This timeline is intended to give an overview of some of the major figures and developments in the history of the Department of History. To scroll through the timeline, please click on the arrows on the left or right, or select a date from the upper bar. All entries feature links to historical documents on the figure or events discussed.

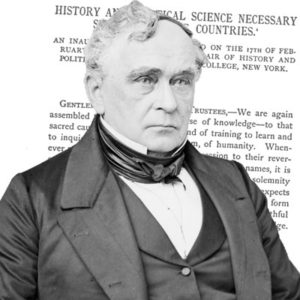

1857

Francis Lieber (1798-1872) was appointed Professor of History and Political Science in 1857. Born in Berlin, Lieber served in the Prussian army during the Napoleonic Wars. He was imprisoned twice on charges of radicalism, and in 1827 immigrated to Boston. During the Civil War, Lieber assisted the Union War Department and drafted a code of military conduct known as the Lieber Code which served as a major inspiration for later developments in international humanitarian law.

Read Lieber’s 1858 address, upon assuming the chair of History and Political Science in Columbia, “History and Political Science Necessary Studies in Free Countries.”

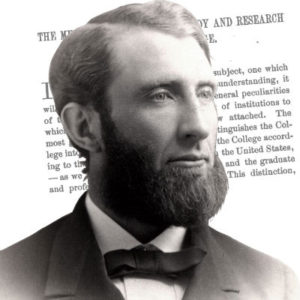

1876

John W. Burgess (1844-1931), appointed Professor for History and Political Science in 1876. Taught courses on medieval history, colonial history, history of the Civil War and United States constitutional history. Burgess played a leading role in pioneering both the field of history and political science in the United States, and is generally considered the “father of American political science”.

John W. Burgess (1844-1931), appointed Professor for History and Political Science in 1876. Taught courses on medieval history, colonial history, history of the Civil War and United States constitutional history. Burgess played a leading role in pioneering both the field of history and political science in the United States, and is generally considered the “father of American political science”.

Read Burgess’ essay “The Methods of Historical Research and Study in Columbia College.”

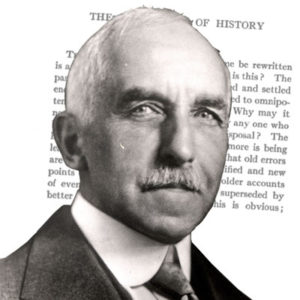

1895

James Harvey Robinson (1863-1936), appointed professor of European history in 1895. Robinson taught courses on the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, the Reformation and the French Revolution. His class “The History of the Intellectual Class of Europe” was one of the most popular at the University in the first two decades of the twentieth century. In his pioneering essay “The New Allies in History” he called for the use of social science—psychology, anthropology and sociology, in the study of history. In 1917 he resigned from Columbia following disputes over academic freedom.

James Harvey Robinson (1863-1936), appointed professor of European history in 1895. Robinson taught courses on the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, the Reformation and the French Revolution. His class “The History of the Intellectual Class of Europe” was one of the most popular at the University in the first two decades of the twentieth century. In his pioneering essay “The New Allies in History” he called for the use of social science—psychology, anthropology and sociology, in the study of history. In 1917 he resigned from Columbia following disputes over academic freedom.

1895

William Milligan Sloane (1850-1928) appointed Seth Low Professor in 1895. Sloane served as head of the History Department from 1896 to 1916. Born in Ohio, he attended Columbia College and later studied in Berlin, where he served as private secretary to George Bancroft, United States Minister to Germany. He was elected president of the American Historical Association in 1911.

William Milligan Sloane (1850-1928) appointed Seth Low Professor in 1895. Sloane served as head of the History Department from 1896 to 1916. Born in Ohio, he attended Columbia College and later studied in Berlin, where he served as private secretary to George Bancroft, United States Minister to Germany. He was elected president of the American Historical Association in 1911.

Read Sloane’s letter of retirement from the department discussing the state of the department and the field of European history, April 20, 1915

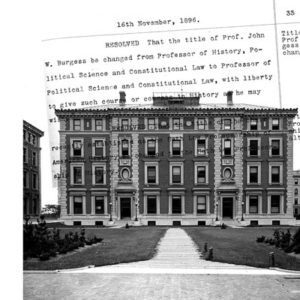

1896

While the teaching of history at Columbia had begun in the mid 19th century, a separate department of history was only formally established on November 16, 1896. Five professors of history taught at the department at the time of its establishment: Herbert L. Osgood, William M. Sloane, John W. Burgess, William A. Dunning and James Harvey Robinson.

While the teaching of history at Columbia had begun in the mid 19th century, a separate department of history was only formally established on November 16, 1896. Five professors of history taught at the department at the time of its establishment: Herbert L. Osgood, William M. Sloane, John W. Burgess, William A. Dunning and James Harvey Robinson.

View the university resolution that formally established the Department of History.

1904

Charles A. Beard (1874-1948), joined Department of History as professor in 1904, after completing his graduate work at Columbia. Beard is generally considered as one of the leading scholars of American history in the first half of the 20th century. He was one of the intellectual leaders of the Progressive movement and of American liberalism. He is best recognized for his pioneering work “An Economic Interpretation of the Constitution of the United States.” Beard resigned from Columbia University during World War I following the dismissal of several faculty members on charges of disloyalty and subversion. He was co-founder of the New School for Social Research in 1919.

Charles A. Beard (1874-1948), joined Department of History as professor in 1904, after completing his graduate work at Columbia. Beard is generally considered as one of the leading scholars of American history in the first half of the 20th century. He was one of the intellectual leaders of the Progressive movement and of American liberalism. He is best recognized for his pioneering work “An Economic Interpretation of the Constitution of the United States.” Beard resigned from Columbia University during World War I following the dismissal of several faculty members on charges of disloyalty and subversion. He was co-founder of the New School for Social Research in 1919.

1907

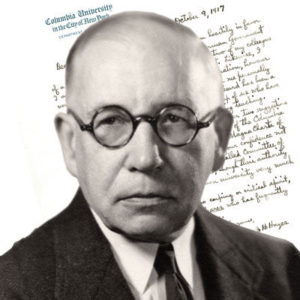

Carlton J.H. Hayes (1882-1964), appointed lecturer in European history in 1907, full professor in 1919 and Seth Low Professor in 1935. Hayes’ scholarship focused on European political, cultural and social history. Hayes served as captain of the United States Military Intelligence Division of the General Staff during World War I, as US ambassador to Spain between 1942-1944 and as president of the American Historical Association in 1945.

Carlton J.H. Hayes (1882-1964), appointed lecturer in European history in 1907, full professor in 1919 and Seth Low Professor in 1935. Hayes’ scholarship focused on European political, cultural and social history. Hayes served as captain of the United States Military Intelligence Division of the General Staff during World War I, as US ambassador to Spain between 1942-1944 and as president of the American Historical Association in 1945.

Read Hayes’ letter to President Roosevelt as ambassador to Spain, June 30, 1942.

1908

James Thomson Shotwell (1874-1865), appointed full professor in 1908. Shotwell’s scholarship focused on medieval Europe and he later wrote extensively on international affairs. In 1919 he attended the Paris Peace Conference as member of President Wilson’s foreign policy advisory group. Shotwell was involved in the creation of the International Labor Organization in 1919 and in 1945 promoted the inclusion of human rights in the United Nations Charter. He served as president of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace (1949-50). Read letters pertaining to Shotwell’s work in the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

James Thomson Shotwell (1874-1865), appointed full professor in 1908. Shotwell’s scholarship focused on medieval Europe and he later wrote extensively on international affairs. In 1919 he attended the Paris Peace Conference as member of President Wilson’s foreign policy advisory group. Shotwell was involved in the creation of the International Labor Organization in 1919 and in 1945 promoted the inclusion of human rights in the United Nations Charter. He served as president of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace (1949-50). Read letters pertaining to Shotwell’s work in the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

1923

William Linn Westermann (1882-1964), joined the Department of History at Columbia as professor of ancient history in 1923. Westermann’s scholarship focused primarily on ancient economic history. He was one of the leading papyrologists in the United States and translated five volumes of Greek Papyri. Westermann served as an expert on Near Eastern affairs at the 1919 Paris Peace Conference and was elected president of the American Historical Association in 1944.

William Linn Westermann (1882-1964), joined the Department of History at Columbia as professor of ancient history in 1923. Westermann’s scholarship focused primarily on ancient economic history. He was one of the leading papyrologists in the United States and translated five volumes of Greek Papyri. Westermann served as an expert on Near Eastern affairs at the 1919 Paris Peace Conference and was elected president of the American Historical Association in 1944.

Read Westermann’s inaugural address as president of the American Historical Association, December 28, 1944.

1924

Lynn Thorndike (1882-1965), Thorndike taught at Columbia between 1924 and 1950. In this time he played a pioneering role in no less than three fields: medieval and intellectual history, and, above all the history of science. Thorndike wrote pioneering surveys of medieval Europe, and of world history, in addition to his classic eight-volume work on the history of magic and experimental science. He was a founder of the History of Science Society and served as its fifth president. Thorndike also served as president of the American Historical Association in 1955.

Lynn Thorndike (1882-1965), Thorndike taught at Columbia between 1924 and 1950. In this time he played a pioneering role in no less than three fields: medieval and intellectual history, and, above all the history of science. Thorndike wrote pioneering surveys of medieval Europe, and of world history, in addition to his classic eight-volume work on the history of magic and experimental science. He was a founder of the History of Science Society and served as its fifth president. Thorndike also served as president of the American Historical Association in 1955.

Read Thorndike’s inaugural address as president of the American Historical Association, December 29, 1955.

1928

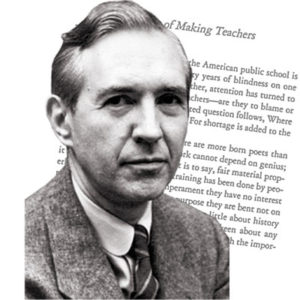

Jacques Barzun (1907-2012) lecturer in history at Columbia from 1928, full professor from 1945 and Seth Low Professor of History from 1960. Barzun published more than 30 critical and historical studies and is considered a founder of the study of cultural history. He pioneered and ran the Great Books course at Columbia College for years. From 1955 to 1968, he served as Dean of the Graduate School, Dean of Faculties and Provost. He was awarded the Medal of Freedom by President George W. Bush and the National Humanities Medal by President Barack Obama.

Jacques Barzun (1907-2012) lecturer in history at Columbia from 1928, full professor from 1945 and Seth Low Professor of History from 1960. Barzun published more than 30 critical and historical studies and is considered a founder of the study of cultural history. He pioneered and ran the Great Books course at Columbia College for years. From 1955 to 1968, he served as Dean of the Graduate School, Dean of Faculties and Provost. He was awarded the Medal of Freedom by President George W. Bush and the National Humanities Medal by President Barack Obama.

View a video biography of Jacques Barzun from 2007 (researched and written by then PhD candidate Jude Webre).

1929

Salo Wittmayer Baron (1895-1989) was the Nathan L. Miller Professor of Jewish History, Literature and Institutions. Baron’s appointment in 1929 marks the beginning of the academic study of Jewish history in American universities. In 1961, Baron testified at the trial of Adolph Eichmann in Jerusalem, providing the historical context to the Nazi genocide against the Jews. From 1950 to 1968 he directed the Center for Israel and Jewish Studies at Columbia.

Salo Wittmayer Baron (1895-1989) was the Nathan L. Miller Professor of Jewish History, Literature and Institutions. Baron’s appointment in 1929 marks the beginning of the academic study of Jewish history in American universities. In 1961, Baron testified at the trial of Adolph Eichmann in Jerusalem, providing the historical context to the Nazi genocide against the Jews. From 1950 to 1968 he directed the Center for Israel and Jewish Studies at Columbia.

View a catalogue of courses in Jewish history at Columbia, 1930-1931.

1938

Henry Steele Commager (1902-1998) joined the faculty of the history department in 1938 and taught until 1956. Commager was one of the most recognized historians of his time and helped define American liberalism. He was a prolific political commentator who disseminated his views to the broader public through newspaper and magazine articles and public speaking. Commager wrote extensively on American intellectual history and is most recognized for his 1950 work The American Mind: An Interpretation of American Thought and Character Since 1880s.

Henry Steele Commager (1902-1998) joined the faculty of the history department in 1938 and taught until 1956. Commager was one of the most recognized historians of his time and helped define American liberalism. He was a prolific political commentator who disseminated his views to the broader public through newspaper and magazine articles and public speaking. Commager wrote extensively on American intellectual history and is most recognized for his 1950 work The American Mind: An Interpretation of American Thought and Character Since 1880s.

Read Alan Brinkley’s review of Commager’s biography, “The Public Professor” (The New Republic, September 27, 1999).

1942

In 1942 the Department of History reorganized its curriculum and introduced nine new courses on the historical background to World War II. These included courses on the British Empire and its problems, American Foreign Policy since 1900 and Far Eastern, Russian and Latin American history. In the following years this process of broadening out the range of the department would continue, most notably in the creation of regional institutes after the war such as the Russian Institute that was founded in 1946.

In 1942 the Department of History reorganized its curriculum and introduced nine new courses on the historical background to World War II. These included courses on the British Empire and its problems, American Foreign Policy since 1900 and Far Eastern, Russian and Latin American history. In the following years this process of broadening out the range of the department would continue, most notably in the creation of regional institutes after the war such as the Russian Institute that was founded in 1946.

Read the New York Times report, “History Curriculum Revised at Columbia,” March 8, 1942.

1946

Richard Hofstadter (1916-1970) joined the department of history in 1946, after earning his doctorate from Columbia. Hofstadter’s scholarship focused on American political culture. Considered a leading public figure and intellectual in the postwar decades, he was awarded the Pulitzer prize twice. Hofstadter was critical of the student demonstrations that broke out on campus in 1968 and defended Columbia as “a center of free inquiry and criticism – a thing not to be sacrificed for anything else.”

Richard Hofstadter (1916-1970) joined the department of history in 1946, after earning his doctorate from Columbia. Hofstadter’s scholarship focused on American political culture. Considered a leading public figure and intellectual in the postwar decades, he was awarded the Pulitzer prize twice. Hofstadter was critical of the student demonstrations that broke out on campus in 1968 and defended Columbia as “a center of free inquiry and criticism – a thing not to be sacrificed for anything else.”

Read Hofstadter’s 1963 essay “The Revolution in Higher Education.”

1960

Norman Cantor (1929-2004), professor at the department of history between 1960-1966. Cantor specialized in medieval history. His books, most notablyThe Civilization of the Middle Ages, are widely read both in academic circles and beyond. In his memoir, “Inventing Norman Cantor,” Cantor vividly describes the department during the cultural upheaval of the 1960’s.

Norman Cantor (1929-2004), professor at the department of history between 1960-1966. Cantor specialized in medieval history. His books, most notablyThe Civilization of the Middle Ages, are widely read both in academic circles and beyond. In his memoir, “Inventing Norman Cantor,” Cantor vividly describes the department during the cultural upheaval of the 1960’s.

Read an article about Cantor’s commitment to teaching, ‘Academic Man-Bites Dog‘ (Columbia Daily Spectator, 29 November, 1962).

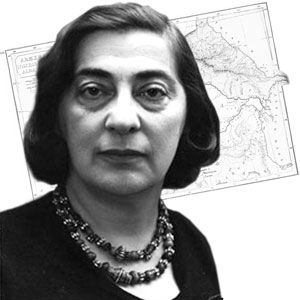

1962

Nina Garsoïan (1923-), Gevork M. Avedissian Professor Emerita of Armenian History and Civilization. Garsoian taught at Columbia from 1962 and was the first female professor to receive tenure in the department in 1969 where she taught until she retired in 1993. She is recognized as one of the leading scholars of Byzantine and Armenian history and has received numerous prizes for her work. One of Garsoïan’s major scholarly contributions was to emphasize in various studies the significance of Persian and Anatolian influences on the development of Armenian history. Read an excerpt from Garsoïan’s memoir De Vita Sua.

Nina Garsoïan (1923-), Gevork M. Avedissian Professor Emerita of Armenian History and Civilization. Garsoian taught at Columbia from 1962 and was the first female professor to receive tenure in the department in 1969 where she taught until she retired in 1993. She is recognized as one of the leading scholars of Byzantine and Armenian history and has received numerous prizes for her work. One of Garsoïan’s major scholarly contributions was to emphasize in various studies the significance of Persian and Anatolian influences on the development of Armenian history. Read an excerpt from Garsoïan’s memoir De Vita Sua.

1967

Women had been hired for full-time professional appointments in the department only from the late 1960s. Marcia Wright, a scholar of East Central Africa, was the first woman to be hired as an assistant professor of history in 1967. Nina Garsoian, who taught at the department of Middle East Language from 1962, was the first woman to receive tenure in the department in 1969. It was not until the early 1970s however, largely as a result of government pressure, that the university committed itself to expanding the number of female faculty. In 1973/4 the department conducted a search and hired three female scholars in the rank of assistant professor in European and American history.

Women had been hired for full-time professional appointments in the department only from the late 1960s. Marcia Wright, a scholar of East Central Africa, was the first woman to be hired as an assistant professor of history in 1967. Nina Garsoian, who taught at the department of Middle East Language from 1962, was the first woman to receive tenure in the department in 1969. It was not until the early 1970s however, largely as a result of government pressure, that the university committed itself to expanding the number of female faculty. In 1973/4 the department conducted a search and hired three female scholars in the rank of assistant professor in European and American history.

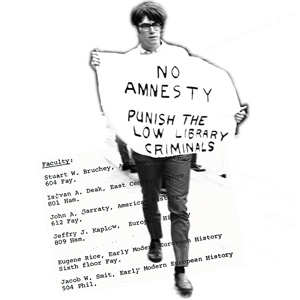

1968

During the 1968 demonstrations at Columbia, students at the department of history called for the creation of a joint Faculty-Student Committee. “We propose that a permanent bipartite student-faculty committee be created whose decisions on policy are to be binding,” read the student memorandum, submitted on April 29. Such a committee was established later that year and included faculty members such as István Deák, John Garraty and Jeffery Kaplow.

During the 1968 demonstrations at Columbia, students at the department of history called for the creation of a joint Faculty-Student Committee. “We propose that a permanent bipartite student-faculty committee be created whose decisions on policy are to be binding,” read the student memorandum, submitted on April 29. Such a committee was established later that year and included faculty members such as István Deák, John Garraty and Jeffery Kaplow.

View the exhibit from the Columbia University Archives “1968 Columbia in Crisis”.

1969

In the spring of 1969 the first course on African-American history was taught at Columbia by a young instructor called Eric Foner. It was a volatile time in the university’s history [see 1968], and with growing numbers of African American students and others pressing for the teaching of black history, the course unfolded against a background of protests and walkouts. Read the Columbia Spectator’s report from March 12, 1969. Shortly afterwards, the department made its first hires in the field of African American history including two pioneers in the field of black studies – Hollis R. Lynch, an Africanist who also wrote on the pan-African movement and Nathan Huggins, a historian of the Harlem Renaissance.

In the spring of 1969 the first course on African-American history was taught at Columbia by a young instructor called Eric Foner. It was a volatile time in the university’s history [see 1968], and with growing numbers of African American students and others pressing for the teaching of black history, the course unfolded against a background of protests and walkouts. Read the Columbia Spectator’s report from March 12, 1969. Shortly afterwards, the department made its first hires in the field of African American history including two pioneers in the field of black studies – Hollis R. Lynch, an Africanist who also wrote on the pan-African movement and Nathan Huggins, a historian of the Harlem Renaissance.

1989

In October 1989 the Department of History announced a new multi-year fellowship program for graduate students in order to professionalize graduate education and recruit teaching assistants for fields such as Latin American, Soviet and Japanese history. Student enrollment in courses in these topics had grown after the university introduced a “major cultures” requirement as part of the undergraduate curriculum. Designing graduate education in the history department was a process long in the making. In 1939, for instance, the department first introduced a requirement for exams in a student’s major field, area of research and in foreign languages.

In October 1989 the Department of History announced a new multi-year fellowship program for graduate students in order to professionalize graduate education and recruit teaching assistants for fields such as Latin American, Soviet and Japanese history. Student enrollment in courses in these topics had grown after the university introduced a “major cultures” requirement as part of the undergraduate curriculum. Designing graduate education in the history department was a process long in the making. In 1939, for instance, the department first introduced a requirement for exams in a student’s major field, area of research and in foreign languages.

1993

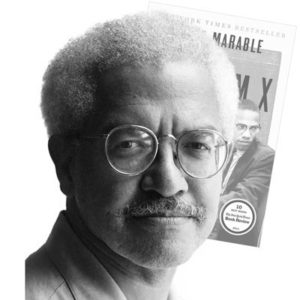

Manning Marable (1950-2011) joined Columbia in 1993 and served as founding director of the Institute for Research in African-American Studies and from 2002 also of the Center for the Study of Contemporary Black History. Manning published numerous studies on African American history. His last work, Malcolm X: A Life of Reinvention was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for History in 2012.

Manning Marable (1950-2011) joined Columbia in 1993 and served as founding director of the Institute for Research in African-American Studies and from 2002 also of the Center for the Study of Contemporary Black History. Manning published numerous studies on African American history. His last work, Malcolm X: A Life of Reinvention was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for History in 2012.

View an interview with Manning Marable on his research on Malcolm X.

Credits:

We would like to thank Barbara Rockenbach and Jocelyn Wilk for their invaluable assistance: help was also received from Pearl Spiro and Rosalind Rosenberg in particular as well as many others. Jim Hall and Amelia Saul designed the site. Gil Rubin conducted most of the research for it. This is an ongoing project and we welcome all suggestions, comments and corrections which may be communicated to facultyaffairs-history@columbia.edu.